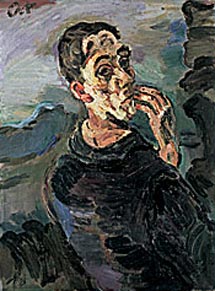

| Alma in the work of Oskar Kokoschka Oskar Kokoschka first met Alma on 12 April 1912 on the occasion of a dinner held at the house of Alma's stepfather, Carl Moll. A frenzied amour fou subsequently developed, which was coupled with an unbridled creative urge; until the end of the liaison in 1915, Kokoschka created around 450 drawings and paintings bearing a relationship to Alma and his passion for her.  |  |

| | Alma Mahler (1912, oil on canvas)

In the early days of their acquaintance, in April 1912, Alma Mahler asked Kokoschka to paint her portrait. Kokoschka had her pose as a new Gioconda and gave her the same mysterious features as those given by Leonardo to his Mona Lisa. He painted the beautiful young woman in a delicate, iridescent hue, blue-eyed and strawberry blonde, with long, loose, dishevelled hair. At the same time, with her narrow, energetic mouth, she appears very determined, almost dangerous. Alma herself perceived herself in the portrait as Lucrezia Borgia, the beautiful Renaissance princess who attracted famous artists such as Ariost to the Ferrarese court and who became notorious as a result of her wild love life.  |  | Double portrait of Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler (1912/1913, oil painting)

At the end of 1912, Kokoschka was working on this double portrait in which Alma wears a red night gown which, for Kokoschka, became a kind of fetish. She writes: "I was once given a flame-red night gown. I didn't like it due to its overpowering colour. Oskar took it from me right away and from then on went around his studio wearing nothing else. He wore it to receive his astounded visitors and was to be found more in front of the mirror than in front of his easel." The picture clearly depicts Oskar and Alma as lovers; they are holding their hands out to one another as if in a formal act of engagement. No doubt Walter Gropius recognized this too, when he got to see the double portrait in spring 1913 at the 26th Exhibition of the Berlin Secession. The message was clear, and must have affected him deeply, particularly since Alma had always kept secret from him in her letters the relationship with Kokoschka which had already endured for over a year. Seven fans for Alma Mahler

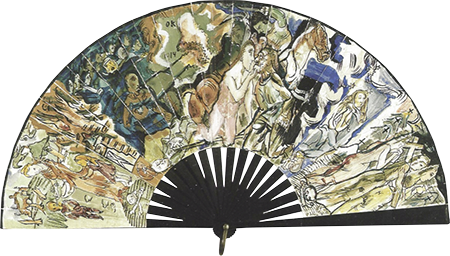

(1912/1913, Indian ink and watercolour on untanned goatskin) Kokoschka described the seven fans which he gave Alma between 1912 and 1914 as "love letters in pictorial form". The first fans were created on the occasion of Alma's birthday in August 1912. The third fan illustrates the couple's journey to Italy together in 1913, and forms the template for the later painting Bride of the Wind (Die Windsbraut). In it, the lovers seek shelter in a boat, reminiscent of their experience together during their stay in Naples. In the background, we see Vesuvius erupting. Only six fans have survived; the seventh was thrown into the fire by Alma's husband Walter Gropius in a fit of jealousy.

Die Windsbraut (Bride of the Wind) (1913, oil on canvas)

Kokoschka's most famous painting shows him and Alma shipwrecked in a tiny boat on a stormy sea. The painting was initially called Tristan and Isolde, the title of the opera by Richard Wagner which accompanied the first meeting between the two in April 1912. The manner in which Alma tenderly snuggles up to him and appears to sleep, while Kokoschka lies there restlessly with eyes open, is telling.  |  | When Kokoschka painted the picture, poet Georg Trakl visited him almost daily and extolled the painting in his poem Die Nacht (The Night): "Golden lodern die Feuer der Völker rings. Über schwärzliche Klippen stürzt todestrunken die erglühende Windsbraut, die blaue Woge des Gletschers und es dröhnt gewaltig die Glocke im Tal: Flammen, Flüche und die dunklen Spiele der Wollust stürmt den Himmel ein versteinertes Haupt." ("The fires of the peoples blaze golden all around. Over dark cliffs, drunk with death, plunges the glowing bride of the wind, the blue swell of the glacier and the bell in the valley clangs mightily: flames, curses and the dark games of lust, as a petrified head storms the heavens.") Even for Alma's 70th birthday in August 1949, Oskar Kokoschka wrote: "We are united for eternity in my Bride of the Wind!"  |  | | | | | | The only remaining photograph

of the fresco above the hearth in Alma's house. | Fresco for Alma's house in Breitenstein (1913, tempera and oil on lime plaster)

Before Alma moved into her new house in Breitenstein on the Semmering in December 1913, Kokoschka painted a fresco measuring four metres across above the fireplace, forming a continuation of the flames beneath, and depicting Alma "pointing to the sky in ghostly brilliance, while he, standing in Hell, appeared surrounded by death and snakes." Little Anna Mahler stood beside the fresco and asked, "So, can't you paint anything else apart from mummy?" The fresco was thought for many years to have been lost, and was only rediscovered in 1988.  | | | Woman bent over phantom (1913)

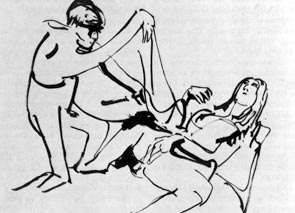

Two nudes: Lovers (1913) |

Alma Mahler with child and death (1913, chalk)

Kokoschka shows Alma with the foetus of their joint child, a crass representation of the termination of her pregnancy in October 1912 which caused him so much pain. With fingertips, death touches Alma's head, and ashamed, she attempts to conceal the aborted child beneath the hem of her skirt.

| | | Alma Mahler with child and death (1913)

Alma spins using Kokoschka's intestines (1913) | Alma Mahler spins using Kokoschka's entrails (1913, chalk)

Kokoschka here once again illustrates the pain which Alma inflicted on him through aborting their child. He uses the story of the torture of St Erasmus of Formio, but substitutes the usual windlass for a spinning wheel, on which Alma winds up the intestines which are bulging out of his stomach. Knight Errant (1915, oil on canvas)

|  | | | | Knight Errant (1915, oil on canvas) | | | | | The agonized knight errant is read as an expression of pain over the death of his unborn child and the crumbling of his relationship with Alma. The central figure appears to be a self-portrait of Kokoschka, clad in the armor of a medieval knight. He lies errant, or lost, in a stormy landscape, his two attributes - a winged bird-man and a sphinxlike woman - in close proximity. The bird-man has been interpreted either as the figure of death or another self-portrait, while the sphinx-woman has been seen as a stand-in for Alma. A funereal sky bears the letters “E S” which probably refer to Christ’s lament, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani” (“My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”). Alma Mahler beset by admirers (1913, chalk lithography)

Alma is thronged by six admirers in a sacred room and appears to be enjoying the attention. By way of illustration for Karl Kraus' The Wall of China, Kokoschka quotes the father of murdered Desdemona: "Fathers, henceforth never trust your daughters!" In a study for this lithograph, Kokoschka explicitly portrays composer Hans Pfitzner, who at the time was investing a great deal of effort in helping Alma.  |  | | | | | Alma Mahler (1913, chalk) | Allos Makar

(1913, lithograph cycle, 4 sheets)

Kokoschka formed the title of a poem, Allos Makar (meaning in Greek: "Happiness comes from a different way"), from the letters of the names Alma and Oskar, and he illustrated the poem through this cycle of graphics: "Wie verdrehte wunderbar mich, seit aus einer Nebelwelt, sie zu suchen, mich ein weißes Vöglein aufgerufen, ALLOS,

ALLOS, der ich nie gegenüber kam. Weil im Augenblicke schnell sie sich verwandelt in mein Wesen, wie eine Hintertür.

Leidet Ohren. Trachtet Augen, sie zu schauen! Ich bin die arme Sommernacht, die verschwand und weint aus einer Erdspalte." ("How was I twisted magically, since from a hazy world, prospecting her, a small white bird summoned me, ALLOS, ALLOS, whom I never came across. Since in an instant swiftly she transformed herself into my being, like a back door. Suffer, ears. Strive, you eyes, to spot her! I into the indigent summer night, which faded and cries from a rift in the earth.") Alma with child (1913/14, drawing)

In this drawing, Kokoschka visualizes his deepest wish for a child with Alma Mahler. In fact, Alma became pregnant twice by Oskar Kokoschka; she lost one child during pregnancy, and had the second child aborted. Kokoschka never got over this termination. He repeatedly hoped that Alma would fall pregnant again, and expressed his yearning for this in numerous works of art. This phenomenon was particularly intensive during and shortly after the trip to Italy which Kokoschka and Alma undertook in April 1913; on Capri, for instance, he completed a wall drawing depicting Alma lying on the beach with a baby and, a few months later in Vienna, he completed the drawing shown below with Alma Mahler and a boy bearing the facial features of Oskar Kokoschka. This mother-child depiction stands, in stylistic terms, at the beginning of the important series of portrait drawings and one painting which Kokoschka referred to as "Mania".  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | Alma with child (1913/14) | | Self drawing (1913) | | Pieta (1914) | Still Life with Putto and Rabbit (1914, oil on canvas)

|  | | | | Still Life with Putto and Rabbit (1914, oil on canvas) | | | | | In this painting dating from 1914, in a curious allegory, Kokoschka constructed the breakdown of his love affair with Alma, which he had celebrated just a short time earlier in his principal work Die Windsbraut. "One should not intentionally prevent the becoming of a human life out of carelessness. It was an intrusion also in my development, that is obvious after all." The "intrusion" which Kokoschka refers to here in his memoirs means the joint child which Alma was expecting, and which she had aborted in 1914. In encoded form, Kokoschka attempted to get close to this event: in a mysterious, gloomy landscape, there sits in the foreground a cat, poised ready to pounce. Its head is turned back towards a rabbit sitting behind it, and with its gaze it has the little animal completely under its spell. Aside from this scene, a tiny male child cowers. The similarity between the portrait of the cat and Alma has repeatedly been raised. The identification with the child not carried to term makes the gestures which stress suffering and the oppressive power of the tree trunk become emblems of death. Alma has turned away from him, and her admonishing glance is intended solely for the rabbit. Thus, Still Life with Putto and Rabbit, bathed in an apocalyptic mood, already heralds the imminent end of the relationship.  |  |  | | | | | Fortuna (1914/15) | | Study for Woman in Blue (1919, Indian ink) | Fortuna (1914/15, lithograph)

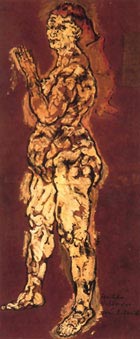

Title picture of the Vier Lieder by Alma Maria Schindler-Mahler, published by Universal Edition Vienna Female nude, standing - Alma Mahler (1918)  |  | | | | This life-size nude sketch of Alma Mahler was prepared in 1918 by Kokoschka for Hermine Moos as a template for the Alma doll. Alma's most significant physical features were particularly emphasized, and her fat deposits were reproduced faithfully using white splodges. Due to the particular purpose of the sketch, which was only rediscovered recently, it retains a special place in Kokoschka's body of work, since the picture was not originally intended for public consumption, but exclusively as a template for doll maker Hermine Moos. In an accompanying letter, Kokoschka wrote instructions for use for the doll maker: "I am very curious as to the padding; in my drawing, I have indicated somewhat schematically what I consider to be the important areas, the hollows and wrinkles; through the skin – the invention of which, and various expression in material, corresponding to the character of the parts of the body, I truly await with great excitement – will everything become richer, more tender, more human?" Here, Alma is shown as a "chastened sinner in full flesh" with her hands raised in prayer. A sinner for the reason that, in Kokoschka's eyes, she committed an irreparable deed in having their joint child aborted without asking Kokoschka beforehand for permission, something he would never have given. The Doll Fetish with Cat (1919, green chalk) Woman in Blue (1919, oil on canvas)

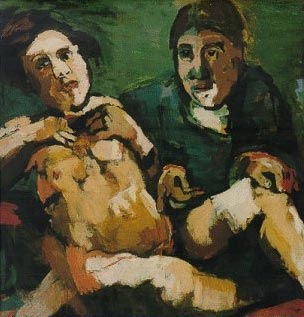

The painting, dating from 1919, was reworked several times and prepared in around twenty studies. The model used was the life-size doll which Kokoschka had made by Munich doll maker Hermine Moos according to detailed instructions and an oil sketch. Endowed with Alma's features, the "silent woman" was to be a compliant substitute companion and muse. The Woman in Blue is one of the first images from the series engaging with Alma and the fetish doll. It is interesting that it was painted after the Alma fetish doll. A friend of Kokoschka's recalled how he once visited Kokoschka while he was working on the picture and, at the time, the life-sized doll lay enveloped in a blue coat on the sofa. Since the likeness of Alma appears fairly approximate and spontaneous, it is all the more remarkable that Kokoschka completed over 100 sketches for the picture. Self-Portrait with Doll (1920/21, oil on canvas)

This picture, originating in 1920/21, shows Kokoschka with his Alma fetish. Against the rich green background, punctuated by a sprinkling of light blue, and which is perhaps intended to suggest a space in the open countryside, the ultramarine shade of Kokoschka's attire stands out as he sits behind the doll.  |  | The fabric woman is supporting her plump body on a vibrant red cushion while the cover on which she is sitting has an orange hue. Her badly proportioned body, viewed up close, is a mottled patchwork of pink, ochre, brown and cream shades. Even a stark shade of red can be made out on her nipples and in her pubic area. Only at a distance do the patches of colour combine to form a picture, even though one still has the impression of bandages, particularly around the knee. The fabric woman is supporting her plump body on a vibrant red cushion, but unlike her lifeless torso, her face however appears very lively. Kokoschka points sadly and in resignation to her womb, and like an accuser, presents her to an invisible court as the originator of his pain.  |  |  | | | | | Lovers (1918/19, reed pen) | | Devotion (1919,

Indian ink) | Orpheus and Eurydice

Kokoschka's Expressionist drama Orpheus and Eurydice (1918) reflects the failure of his love for Alma in the myth of the ancient love story. It was set to music by Alma's son-in-law Ernst Krenek as an opera in three acts, op. 21, with Kokoschka himself as Orpheus, Alma as Eurydice, and her daughter Anna Mahler as Psyche, while Gustav Mahler was invoked as Pluto, god of the Underworld.  |  | | | | Self-Portrait (1918/19)

Poster for art exhibition (1919) | | |