| Heaven and hell (1911-1917) Following Gustav Mahler's death, Alma was a radiant presence in the prime of her years and, thanks to a widow's pension and Gustav Mahler's inheritance, an affluent woman. Soon she was much courted in Vienna.  |  | | | | | Alma in 1907, the year in which Gustav Mahler's heart disease was diagnosed | |  |  | | | | | | Alma with her daughter Anna following the death of her father Gustav Mahler, Vienna 1912 | As early as the autumn of 1911, Alma had a brief relationship with composer Franz Schreker. Joseph Fraenkel too, Mahler's doctor in New York, was also suddenly at her door in Vienna. Alma called him a "poor, sick, elderly little man, who was preoccupied only by his serious bowel disorder" and rejected his proposal of marriage. She gave more attention to biologist Paul Kammerer, who was a fervent admirer of Mahler's music and offered Alma a position as assistant at his biological institute in the Viennese Prater, where she collaborated for several months on experiments with praying mantises. When Kammerer threatened to shoot himself at Mahler's grave, she ended the relationship in the spring of 1912.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Franz Schreker, composer | | Joseph Fraenkel,

Mahler's doctor in NY | | Paul Kammerer,

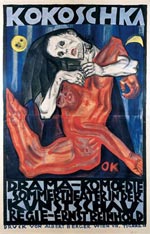

biologist | Walter Gropius was shocked to learn that, before Mahler's death, the couple had had a physical relationship, and he avoided a reunion with Alma in Vienna. In December 1911, the two finally broke up. The relationship was already overshadowed by Alma's excessive association with the enfant terrible of the Viennese art scene, the young Oskar Kokoschka, who caused a considerable sensation in the seething Viennese cultural arena of the period before World War I and was considered a revolutionary, eccentric and provocateur, as well as a brilliant painter.  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Poster "The Storm", 1910 | | Oskar Kokoschka 1909 | | Self-portrait, 1912 | Carl Moll commissioned Kokoschka to create a portrait of Alma. Straightaway, during dinner on the evening of 12 April 1912, Kokoschka fell in love with the widow: "How beautiful she was, how seductive behind her mourning veil! I was bewitched by her!" The next day, she received his first love letter, which was to be followed by four hundred more. The two lived and travelled together, and when they were not sleeping together, he painted her.  |  | | | | | Double nude, 1913 | | Kokoschka's outbursts of feeling were unpredictable; he loved passionately and unconditionally, "like a pagan praying to his star". Alma must have experienced the violent passion in a similar way: "The three years with him were a battle of love. Never before have I tasted so much hell and so much paradise." From the outset, Alma suffered from Kokoschka's unbridled jealousy; he could scarcely bear her to engage in social contact with other people. "You may not slip away from me even for a moment; whether you are with me or not, your eyes must always be directed at me, wherever you might be." Kokoschka's jealousy was however directed not only towards Alma's friends and acquaintances, but in particular also towards her dead husband, Gustav Mahler.  | |

Auguste Rodin: Mozart (Portrait bust of Gustav Mahler), marble, 1911

| Before the premiere of the 9th Symphony on 26 June 1912, an argument arose: "Why have you invited me to a danse macabre, intending me to watch you for hours without saying a word as you, a spiritual slave, obey the rhythm of the man who was and must be a stranger to you, and to me too, knowing that every syllable of his work undermines you, both spiritually and physically?" As early as July 1912, Alma became pregnant by Kokoschka. In October however, she had the pregnancy terminated. In the hospital, he took the first blood-soaked cloth from her and carried it home. "That is my only child, he said, and will always be so." Later, he always carried this old, dried-up piece of cloth with him. Kokoschka never overcame his pain at the loss of their joint child, and made it the topic of numerous drawings. Kokoschka tried everything to persuade Alma to marry him, but she withdrew more and more. Kokoschka was looking for a "maternal genius" and expected - despite all ecstatic excesses - to receive care and loving dedication.  |  | | | | | Oskar Kokoschka: "Bride of the Wind" (1913) | | | | | In the long term, the relationship could not function. In 1913, he painted "Bride of the Wind", an emphatic, baroque picture in which the two lovers are shown swirling through the room. Even on her 70th birthday, Kokoschka called his immortal beloved a "wild creature" and was convinced that "In my Bride of the Wind, we are united for eternity."

Alma recounted Kokoschka's love in these terms: "Oskar could only love with the most dreadful notions in this head. Since I refused to hit him during our hours of passion, he started to concoct the most horrific images of murder in his head and whisper them quietly to himself. I remember for instance that he once conjured up Dr Fraenkel, Mahler's doctor, in this way and I had to participate in a disgusting murder fantasy. When he believed himself to be satisfied, he said, "Even if it might not have killed him, it would have given him a minor heart attack."

|  |  | | | | | | Double Portrait of Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler (1912/13) | | Walter Gropius | Alma was still in correspondence with Walter Gropius, but had left him in the dark as to her relationship with Kokoschka. When, in 1913, Gropius saw Kokoschka's painting "Double Portrait of Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler", which was on display at the 26th exhibition of the Berlin Secession, the correspondence came to a complete end. Alma regularly eluded Kokoschka's repeated attempts to persuade her to marry him by long trips in the company of her friend Lilly Lieser, and in May 1914 she lamented in her diary that the relationship was over: "I would like to settle up with Oskar. He no longer suits my life. He drags me back into the realm of the libidinal. I can't do anything with that any more. And however sweet and helpless that big baby is, he is also unreliable and indeed treacherous as a man. I must tear him out of my heart! The stake is embedded deep in my flesh. I know that I am sick because of him - have been sick for years - and have been unable to tear myself away. Now, the moment is there. Away with him! - My nerves are shattered - my imagination ruined. What fiend sent him to me?" At the beginning of December 1914, Oskar Kokoschka learned of his conscription. "Since I was liable for military service, it was advisable that I should report as a volunteer recruit before I was forced to join in." However, Anna Mahler was later to report that her mother was not entirely uninvolved in this decision. "Alma persisted in calling Kokoschka a coward until he finally "volunteered" for war service. He didn't want to go to war, but she had had enough of him, he had become too tiring."  |  |  |  | | | | | | | Alma Mahler 1917 | | Oskar Kokoschka 1915 | | Through the mediation of his friend Adolf Loos, Kokoschka was recruited into the No. 15 Dragoons Regiment, the most elite cavalry regiment of the Austrian monarchy. Ironically, he purchased the horse he needed with the money which he obtained from selling "Bride of the Wind".

On 29 August, Oskar Kokoschka was seriously wounded on the Russian front, and the newspapers even assumed he had been killed. Alma reacted to the news by fetching from Kokoschka's studio the letters which she had written him and also taking sketches and drawings for herself.

|  | | | | | Pieta (1909) | | Via Adolf Loos, Kokoschka asked Alma to visit him on his sick bed, but she had put him behind her; "The whole thing doesn't affect me very much. I don't really believe in his injuries. I just don't believe this person at all any more." Besides Kokoschka's countless paintings and drawings, a brazen life-sized doll, a true image of Alma down to the most intimate details which Kokoschka had made by Munich doll maker Hermine Moos, testifies to the suffering he endured as a result of his relationship with Alma. The doll was intended to console him over the loss of his beloved. It has not been preserved, since in 1919 it was destroyed in an excessive nocturnal orgy of destruction at Kokoschka's studio in Dresden. > Read more about the doll

While her relationship with Kokoschka was still ongoing, Alma resumed contact by letter with Walter Gropius. In February 1915 she travelled to Berlin in the company of her friend Lilly Lieser with the aim of "getting through again to this bourgeois son of a Muse". Their wedding finally took place on 18 August in Berlin. Gropius was the only man who, according to Alma, was her "racial equivalent". At the same time, she turned her attention to the musical legacy of Gustav Mahler. She still saw herself mainly as his widow, and experienced her marriage to the as-yet-unknown architect Walter Gropius as a step down the social ladder. She wrote to him, "that the doors to the whole world, which stand open for the name of Mahler, slam shut in the face of the entirely-unknown name 'Gropius' ".  |  | | | | | Alma with Gropius and their daughter Manon, 1918 | | Alma was shocked when her husband was transferred as regimental adjutant to a military communications school, where he was in charge of dog training. She called the assignment subaltern and undignified, and demanded "My husband must be first class!" On 5 October 1916, it finally happened: "On that Thursday, I gave birth to a sweet new little girl. Amid the most atrocious pain - but now she is here, I am happy. I am in love with this creature!" From the first moment, the girl cast a spell over everyone; "His spirit, my body! The consummation of us both must give rise to a demigod!"

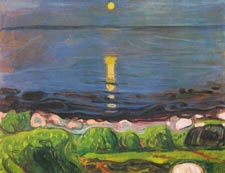

|  | | | | | | Edvard Munch:

Summer Night on the Beach (1895) | When the proud father first set eyes on his daughter, he was enraptured and enthused about her "long, narrow aristocratic fingers" and big eyes "which already look at the world full of awareness". The christening of little Manon Alma Anna Justine Caroline Gropius took place at Christmas 1916 in Vienna. To celebrate the occasion, Walter Gropius gave his wife the painting "Summer Night on the Beach" by Expressionist painter Edward Munch. > next: "Man-child" Franz Werfel (1917 - 1938)

< back: Life with Gustav Mahler (1901 - 1911) | |