| RICHARD WAGNER: Isoldes Liebestod

(Alma's favourite composer/Meeting with Kokoschka)

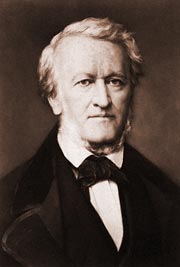

"I love someone, so passionately, perhaps no person was ever been loved so fervently – it is Richard Wagner. He is the dearest person to me on earth – I swear it." (Alma in her youthful diaries, 6th June 1898)  |  |  | | | | | | Richard Wagner | | Tristan and Isolde | Alma and her composition tutor, Alexander von Zemlinsky, whom Alma considered dreadfully ugly – chinless, small, and with bulging eyes, spent an evening conversing at length about Richard Wager, and his Tristan in particular. When Alma revealed to him that this work was her favourite opera, Zemlinsky was so delighted that he became unrecognizable. He became veritably attractive. "Now we understood one another." (Oskar Kokoschka in his memoirs:) "How beautiful she was behind her mourning veil! I was bewitched by her! After dinner, she took me by the arm and led me into the adjacent room, where she sat me down and played me the Liebestod". (Alma:) "We stood up – and suddenly he embraced me impetuously. I was not familiar with this type of embrace ... I did not reciprocate it in any manner, and precisely that seemed to have an effect on him. He stormed off, and one hour later, I had the most beautiful letter of love and courtship in my hands." STRAVINSKY: The Rite of Spring (Parallel to Kokoschka's painting)  |  | | | | | Alma and Igor Starwinsky 1946 in Los Angeles

| | In Paris in 1912, composer Alfredo Casella played Alma Stravinsky's new composition, The Rite of Spring, of which she subsequently declared that it contained "the most dangerous ideas since Mahler". Alma: "These were new musical lands and, after Debussy, the first music which could once more conjure up for one moments of happiness." It was not just that Kokoschka, jointly with Alma, experienced the "jarring animality of gushing sounds", but she linked the Russian composer's early music with Kokoschka's vision of art and "virtuosity of eroticism". For her, Kokoschka's Windsbraut (Bride of the Wind) and Stravinsky's Rite of Spring came from a single source. Later, Werfel labelled her passion both for Kokoschka and for Stravinsky as "an advanced stage of perversion". ERNST KRENEK: Opera after Kokoschka's Orpheus & Eurydice

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera in three Acts, op. 21, Libretto by Oskar Kokoschka.  |  | | | | | Oskar Kokoschka: Die Windsbraut

(Bride of the Wind) (1913) | | The opera is based on a drama by Kokoschka, for which, in 1923, Ernst Krenek wrote the music "as if in a frenzy". Anna Mahler, Alma's daughter, who was married to Krenek – his Second Symphony is dedicated to her – composed the vocal arrangement. The premiere took place in Kassel in 1926. Since then, the work has rarely been played, although in 2005, a concertante version was performed at the Salzburg Festival. The theme of Kokoschka's drama Orpheus and Eurydice, which he wrote while convalescing in 1916/17, after being seriously wounded on the Russian front, is his failed relationship with Alma. Numerous drawings and paintings were subsequently created on the same subject. In 1921, Kokoschka's play was premiered in Frankfurt, directed by Heinrich George, who also played the role of Orpheus. During the rehearsals, Kokoschka sat in the first row of the stalls and cried silently but incessantly. Albrecht Joseph, who was later to marry Anna Mahler, was George's assistant and recalls as follows: "Whenever I had to climb from the stalls over the small makeshift bridge onto the stage to discuss something with George, on my way back I unavoidably saw tears flowing down Kokoschka's face. I was puzzled, for I did not know that Orpheus was Kokoschka himself, Eurydice Alma, Psyche her daughter Anna, and Pluto [Gustav] Mahler. I had no idea that, for several years after Mahler's death, Alma and Kokoschka had a passionate, wild love affair with one another, which ended with Alma urging her lover to go off to war, although he was in no manner cut out to be a soldier. He came home from the front badly wounded, and Anna says her mother refused to visit him in hospital or to see him at all thereafter. He had not succeeded as a soldier, and she could not forgive that. But Kokoschka could not forget her. It was said that he had a life-sized doll made, a likeness of his love goddess, which he took with him when he travelled, and even to bed." BACH: Cantata O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort (Oh Eternity, you thunderous word) BWV 60 (illustration by Kokoschka) The Cantata consists of a dialogue between fear and hope, which Oskar Kokoschka transposed to his own experiences with Alma. Kokoschka: "... a myth, a Structured Symbol, heavy with encounter, procreation and division. I sensed impending doom." "Es ist genug: Herr, wenn es dir gefällt, so spanne mich doch aus. Mein Jesus kömmt: nun gute Nacht, o Welt! Ich fahr ins Himmelshaus, ich fahre sicher hin mit Frieden, mein großer Jammer bleibt darnieden. Es ist genug, es ist genug." ("'Tis enough: Lord, if it pleases Thee, so release me. My Lord Jesus is coming: now I bid good night, oh world! I am journeying to the house of Heaven; hither shall I travel safely and in contentment, and my great sorrow shall remain below. 'Tis enough, 'tis enough.") Oskar Kokoschka: Self-Portrait (Half-length portrait with drawing pencil), 1914, Title page of graphic cycle O Ewigkeit Du Donnerwort ("Bach Cantatas") ALBAN BERG: Violin Concerto (dedicated to Alma's daughter Manon Gropius)  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Alban Berg | | The Death Mask of Manon Gropius | | Manon Gropius | On 5 October 1916, Alma gave her husband Walter Gropius a baby girl who, from the very first moment, cast a spell over everyone. "His spirit, my body! The consummation of us both must give rise to a demigod!" Manon enchanted every visitor: "she exuded timidity more than beauty, an angelic gazelle from Heaven!" (Elias Canetti). In Venice in April 1934, one evening she complained of a raging headache; the doctor was called, and within just a few hours, she was paralysed from polio. She was just seventeen years old. Back in Vienna, the captivating Manon, who would have liked to become an actress, sat dolled up in a wheelchair and was led around the vast house on the Hohe Warte. She died quite suddenly, on Whit Monday in 1935. In memory of Manon Gropius, Alban Berg composed his Violin Concerto, dedicating it "To the Memory of an Angel". ANTON BRUCKNER: Symphony No. 3 (A deal with Adolf Hitler)

"I was wearing sandals, and lugged along a bag containing the rest of the money and jewellery and the score of Bruckner's Third Symphony." This is how Alma describes her flight from the Nazis out of southern France towards Lisbon, from where she fled to the USA. Gustav Mahler's widow was one of over 15,000 German refugees who, in 1940/41, waited hopefully in the south of France for their exit papers. The bag containing the music, the rolled-up canvases, the suitcase of manuscripts, represented the last possessions which she hoped to save, in addition to her very life.  |  |  |  | | | | | | | Anton Bruckner | | Gustav Mahler 1878 | | For his teacher, Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler had prepared a piano arrangement of the Third Symphony, for which the composer gave generous thanks, giving Mahler the manuscripts of the first three movements.

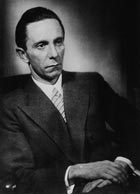

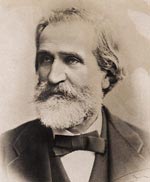

Following Hitler's entry into Vienna, the Nazi regime became extremely interested in those Bruckner manuscripts situated in private ownership. The Führer was a great enthusiast of Bruckner, and publication of the "original versions" of his symphonies, which were to be "cleansed" of outside influences, was deemed a cultural-political goal. Compilation of the valuable manuscripts was coordinated within Joseph Goebbels' Ministry of Propaganda. Procurement of the scores assumed top priority, "because we fear that something could happen to these valuable treasures."  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Joseph Goebbels | | Alma with Richard Eberstaller | | Ida Gebauer, "Schulli" | This fear was entirely justified, since Alma had arranged for her husband's precious possession to be smuggled to France long before with the help or her lady in waiting. When the Nazis asked after the music, Alma's brother-in-law could only report its loss. However, Alma offered the state two options: "either the purchase of these manuscripts at a price of c. RM 15,000 [c. EUR 52,000] or purchase of the house or villa having a value of c. RM 160,000.00". It is unclear how Alma envisaged such a deal. At the Ministry of Propaganda, Alma's offer went through the various levels of authority, until she was asked to deposit the Bruckner manuscript at the German Embassy in Paris. She was promised that the diplomats there would pay in cash the sum required – by now she was asking for £1,500 (at today's prices, c. EUR 72,000).  |  | | | | | Alma's passport photo, 1938 | | When, on 3 May 1939, Alma appeared at the Embassy with the Third Symphony under her arm, she made the unpleasant discovery that the officials in attendance knew nothing of the arrangement made. Under such circumstances, she was on no account prepared to hand her precious possession over to the Germans. The reason the sale fell through was quite straightforward; the Ministry of Propaganda had omitted to inform the officials in Paris in time as to Alma's visit, and the relevant instructions were not received at the Embassy until 4 May. Alma's brother-in-law, Richard Eberstaller, an ardent Nazi, finally succeeded in persuading Alma to make a renewed visit to the German diplomatic mission. Now there were no further obstacles to the sale. However, after several weeks, the authorities in Berlin enquired impatiently whether Alma had by now called at the Embassy. In response, on 6 June, Paris reported that Ms Mahler-Werfel had not been seen again. Alma and Franz Werfel has returned to Sanary, in the south of France, back in mid May. However, the story was not to end until they reached America. It was said that, in mid December 1940, Ms Mahler-Werfel could be reached by telegram in her New York hotel and awaited transfer of the amount owed in pounds sterling or US dollars. Alma's brazen approach caused astonishment: "All well and good, but where will the foreign currency come from?" Several weeks later, the Budget Department's appraisal arrived; the amount demanded by Ms Mahler-Werfel was however so high that it would "need to be transferred from the gold reserves of the Reichsbank." The responsible official stated that such a measure could not be justified in the current circumstances; "after all, Ms Mahler-Werfel is likely to be to some degree a non-Aryan emigrant, to whom we have few grounds to pay such sums in cash." In official parlance, purchase of the score was rejected for reasons of exchange-rate policy. Alma's deal with the Führer had definitively failed; she had overstepped the mark. VERDI: (Franz Werfel's favourite composer)  |  |  |  |  | | | | | | | | Franz Werfel 1924 | | Verdi: Roman der Oper (1924) | | Giuseppe Verdi | Franz Werfel was a big fan of Verdi; he translated the libretto of La Forza del Destino and, with his novel Verdi: Roman einer Oper celebrated his first big commercial success as an author. When the Verdi novel was published on 4 April 1924, Alma had every reason to be proud of her "man-child" Franz Werfel. The first edition was sold out within just a few months, and achieved an impressive success. Werfel's first novel became the foundation stone of publishing house Paul Zsolnay. HANS PFITZNER: String Quartet D major (dedicated to Alma)  |  | | | | | Hans Pfitzner | | | | | Hans Pfitzner dedicated to Alma his string quartet D major op. 13 (1902/03, first performed 1903 in Vienna by the Rosé Quartet). Alma describes in her autobiography that Gustav Mahler explicitly described Pfitzner's second string quartet as a masterpiece. Alma reciprocated Pfitzner's adoration with contempt despite her agreement with his intuitive musical idealism, a fact evident in her letters to Helene, the wife of Alban Berg. ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD: Violin Concerto (Dedicated to Alma)  |  |  |  | | | | | | | Erich Wolfgang Korngold | | Alma | | Korngold's Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D Major, Opus 35 (published in 1945) is dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel, who was a long-time friend of the family and had formed part of the artistic circle in exile in California of which Korngold too had been a member since emigrating in 1934. At the beginning of the 1940s, Los Angeles became a stronghold of German emigration; writers Thomas and Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht and Alfred Döblin, composer Arnold Schönberg, director Max Reinhardt, to name but a few, settled in "German California" at some point following their flight from Europe. "Initially I was a wunderkind, then a successful opera composer in Europe, and then a film-music composer. I think that I must now make a decision if I do not want to spend the rest of my life as a Hollywood composer" – this is how Korngold described a turning point in his life, in 1946. The end of the War, in 1945, not only offered the composer the opportunity to travel to Europe again, but it also marked a creative crisis. Korngold now turned his back on film music and began once more to compose "absolute" music in traditional genres. His Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 35, from 1945, marked the beginning of this new creative phase. At the time, Korngold aimed the immense virtuosity of the solo part at the particular skills of the great violinist Jascha Heifetz, and indeed composed the Concerto specifically with Heifetz in mind. Heifetz gave the premier of the Concerto on 15 February 1947 in St Louis with the St Louis Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Vladimir Golschmann. In the final movement, Korngold reprises the main melody from the 1937 Hollywood production The Prince and the Pauper. Arranged as a sequence of variations on the folksy, rustic theme, the closing movement represents a tour de force as a violin performance, giving the soloist the opportunity to demonstrate his virtuosity in all its brilliance. Recently, Anne-Sophie Mutter has popularized this little-known treasure among violin concertos. It is a wonderful romantic piece, very evocative of film music – cinema for the ears! Mutter is accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of her husband, André Previn who, with the LSO, won a Grammy for his Korngold interpretation. ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG: Canon (dedicated to Alma)

On the occasion of the 70th birthday of Alma Mahler-Werfel on the 31st of August in 1949, Arnold Schönberg dedicated a four-part canon to her. BENJAMIN BRITTEN: Nocturne Op. 60 (Dedicated to Alma) Britten: Nocturne, Op. 60. For tenor, seven obbligato instruments, and string orchestra (1958). Britten dedicated the work to Alma Mahler in acknowledgement of his indebtedness to Gustav Mahler. The Nocturne Op. 60 was premiered at the Leeds Centenary Festival in 1958, the year of its composition. Its subject matter is night-time, sleep and dreams. Britten uses seven different soloists, each of whom lends their characteristic colour to a song. The Nocturne is through-composed and held together by means of a recurring ritornello figure in the strings, its gently rocking motion intended to represent the breathing sleeper. The strings accompany the lullaby-like first song, Shelley's On a poet's lips I slept, dominated by the sleeping motif mentioned above. This cross-fades into the second part, Tennyson's The Kraken, the great sea monster suggested by the wide range and writhing of the solo bassoon. The harp is used to characterize Coleridge's delicate moonlit reverie of the "lovely boy plucking fruits", its pure, untroubled A major - Britten's usual key for symbolizing innocence and beauty – appearing only mildly disrupted in the final line, "Has he no friend, no loving mother near?" The horn supplies onomatopoeic nocturnal sounds for Middleton's "midnight bell", with colourful use of muting, hand-stopping and flutter-tongue. The two central settings focus on the more sinister aspects of night and darkness; the lines taken from Wordsworth's The Prelude are coloured by the timpani, their shadowy rumbling driving the music to an anguished climax which, after a rapid diminuendo, is followed by a setting of Wilfred Owen's The Kind Ghosts (anticipating Britten's use of this poet's verse in the War Requiem). At this point, we now hear a funeral march featuring a plaintive lament from the cor anglais, accompanied by the mournful pizzicato tread of the strings. The setting of Keats' Sleep and Poetry is quite different; with its airy dialogue between flute and clarinet, this section is the lightest setting in the entire work. This culminates in a return of the ritornello, which in turn leads into the richly expressive, Mahlerian final song, a setting of Shakespeare's Sonnet 43, "When most I wink", in which all the instruments used hitherto are combined. <Back to Part I of Alma in the music of other composers | |